No one can deny that batteries are a major issue when it comes to assessing the environmental impact of electric cars. Just last year, the three ‘fathers’ of the lithium-ion battery were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their core research in the 1980s. Without them, we would not have mobile phones, laptops, hearing aids or electric cars. And with electric vehicles about to make that big breakthrough worldwide, researchers and industry are looking to optimise raw material cycles and recycling processes.

The second life of used batteries

The manufacturer’s warranty for electric car batteries normally provides cover for eight to ten years or around 150’000 kilometres. By this time, they can still deliver around 70% of their original power. This is plenty enough for further use as a stationary storage battery. Examples include

- solar storage battery in buildings with photovoltaic installations.

- power bank in mobile fast charging stations for electric cars. The VW system, for example, can charge up to four electric vehicles at the same time and store electricity on a temporary basis. Audi, Daimler and BMW are also adopting the ‘second life’ concept.

- storage battery for power stations, to be tapped when energy demand is particularly high.

« Time for a ‘second life’ following use in electric cars. »

Members of the public are even finding further uses for old Li-ion batteries. For instance, Marco Piffaretti, an expert and pioneer in electric mobility in Switzerland, has a photovoltaic unit at home that feeds a used battery in his garage. This in turn serves as a daily buffer store for his electric car’s charging station. ‘The battery’s performance is doing better than expected,’ he points out with satisfaction. ‘This goes to show how a second life can last much longer than was assumed just a few years ago.’ It would appear that ten years’ further use is not unreasonable. Particularly with the demands made of batteries used in stationary applications being ten times or so less onerous than in a vehicle.

Hot or cold: the hunt is on for the best recycling process

Recycling old traction batteries helps support the circular economy. The idea is to reclaim as much valuable material as possible, particularly with recycling processes being quite capital-intensive. And as Christian Hagelüken, from the Belgian recycling company Umicore, is keen to point to out: ‘Recycling will only really establish itself when it proves to be economically viable.’

There are currently two options: batteries are melted down or shredded and treated with chemicals. Melting down is also referred to as the ‘hot process’, while the second approach is known as the ‘cold process’. With the hot process, the metallic components, i.e. cobalt, copper and nickel, are relatively easy to reclaim – as much as 95% in the case of cobalt. So far, the hot process is the only viable option for the simultaneous recycling of a wide range of battery types, although critics complain about its high energy requirements.

« The ‘hot process’ uses a lot of energy. »

This is why many companies are focusing on the cold process. This year, for example, Volkswagen is commissioning a pilot plant in the town of Salzgitter, which can process 3’000 batteries a year as things currently stand and aims to achieve a recycling rate of 90%. The German firm Duesenfeld is also conducting research into alternatives to melting down batteries and has set up a pilot factory near Braunschweig. Before 2020 is over, the aim is to reclaim 96% of all battery materials at a purity that would permit them to be reused in the manufacture of batteries.

Switzerland also searching for more efficient approaches

Just like Germany, the Swiss too are busy trying things out. ‘auto-schweiz’, the Swiss association of car importers, is looking for a sector-wide solution for the recycling of batteries. The recycling foundation known as ‘Auto Recycling Schweiz’ was duly commissioned to come up with one and has been working on this project since March 2019 with the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA). As regards evaluating the best recycling system, EMPA feels that comminution (the breaking down of materials) is not the only issue. It is also a case of building a supply chain to reduce the flammability of batteries recovered from vehicles damaged in accidents.

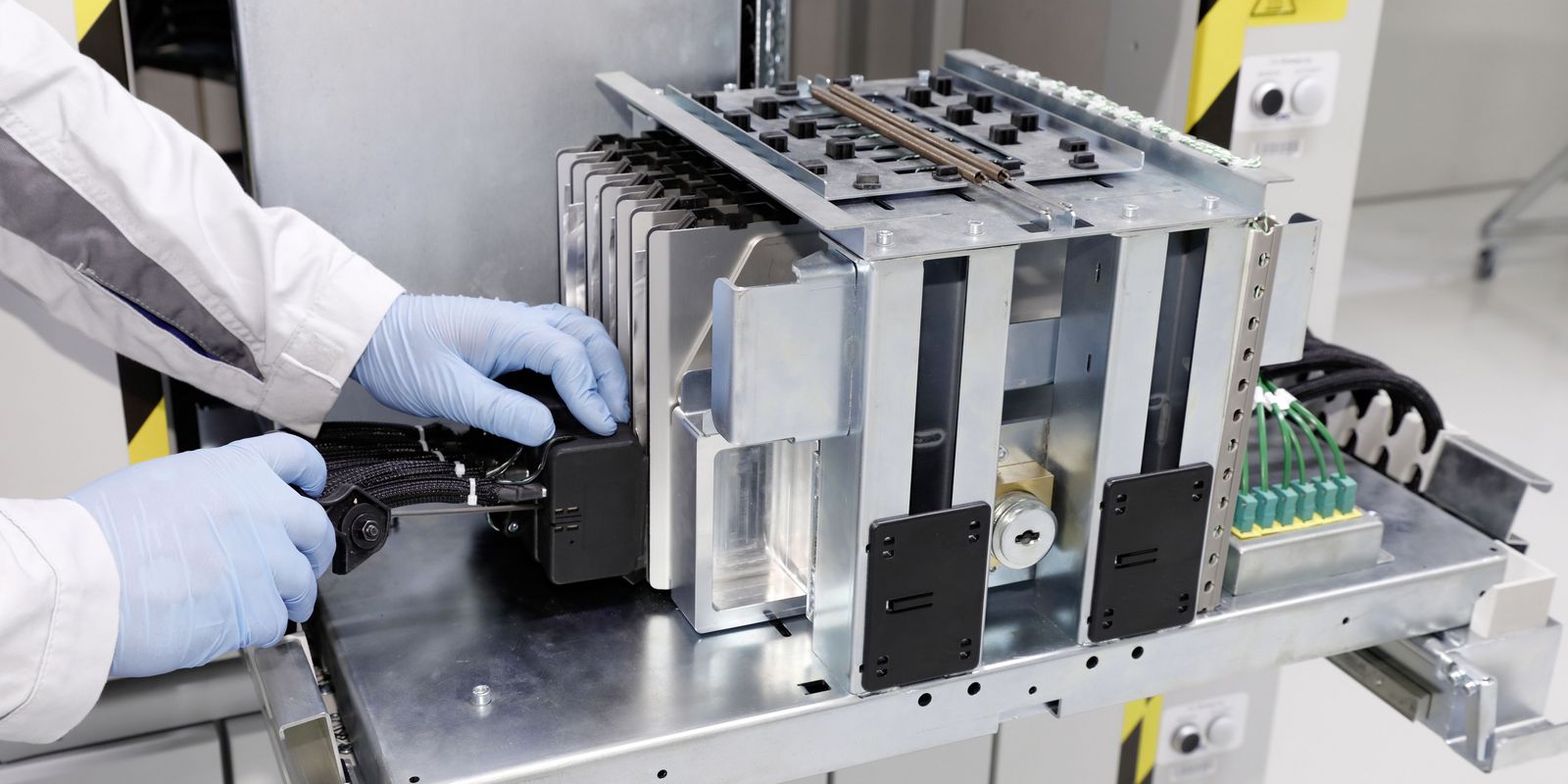

Switzerland does have a number of other innovative recycling companies, and the electric mobility firm Kyburz Switzerland AG (based in Freienstein) is a good example. The manufacturer of Swiss Post’s ubiquitous trikes opened its own battery recycling plant in September. EMPA sponsored this project too. The fundamental principles underpinning the recycling process are optimal discharging, careful dismantling of the cells, and purification with water rather than chemicals.

Part of a holistic view of environmental impacts

Marco Piffaretti, who is also driving the ‘e-offensive’ at the car sharing provider Mobility, is keen to underline the importance of widening the frame of reference when it comes to assessing the environmental aspects of e-mobility. ‘The current focus is very much on consumption and emissions data while vehicles are actually being driven. In future, the cycle as a whole will become more relevant – from vehicle manufacture through to recycling and reusing materials.’ And this applies not just to car manufacturers, but also to buyers like Mobility, which is looking to convert its entire fleet to electric cars and achieve climate neutrality by 2040. ‘Any effort that makes electric mobility that bit more sustainable is to be welcomed,’ concludes the expert.

Your comment